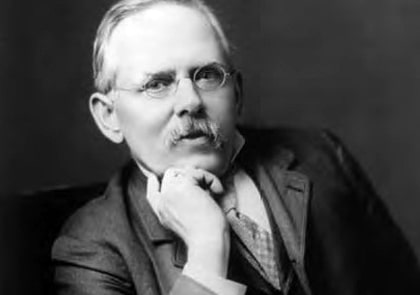

Jacob A. Riis emigrated from Ribe, Denmark to New York City in 1870, at the age of 21. From there, he began a remarkable journey from a working-class immigrant to one of the most influential journalists and social reformers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Riis immigrated at a time when the population of Manhattan’s Lower East Side was rapidly increasing, as thousands of European immigrants moved into the area’s crowded tenement buildings. After working several menial jobs, Riis became a police reporter in 1877 for the New York Tribune, before joining the New York Evening Sun in 1888. While working as a police reporter, Riis often wrote stories of the New York City slums and learned about the immigrant neighborhoods that would later become the basis of his calls for social reform. Riis was among the first photographers to use flash powder, which enabled him to photograph the interiors and exteriors of the slums at night.

In 1890, Charles Scribner’s Sons published How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, Riis’ groundbreaking expose of conditions in the city’s slums on the Lower East Side. The book used revealing photojournalism and detailed analysis of the housing problems afflicting poor immigrants to argue in favor of reforming New York’s tenements. This book launched Riis’ career in social reform. He spent the rest of his life raising awareness about the grim realities facing poor immigrants inside New York City’s slums. Riis’ work brought him to the attention of Theodore Roosevelt, who served as president of the New York Board of Police Commissioners from 1895 to 1897. Roosevelt and Riis soon became friends, and Roosevelt often went with Riis on some of his late-night adventures into the New York slums to investigate living conditions.

Riis believed that individuals, regardless of their economic status, should be given a chance to improve their lives. Given that chance, he believed many could rise out of poverty and into the ranks of the middle class. Reformers like Riis believed that poverty was the result of social and economic conditions, not moral weakness, and that reform efforts could help the poor.

Strongly influenced by the work of settlement house pioneers in New York, Jacob Riis helped the Circle of the King’s Daughters, an organization of Episcopal Church women who supported his earlier advocacy for the poor, secure temporary space in the basement of the Mariner’s Temple on the Lower East Side near the Bowery and Chinatown. Initially focused on helping the corps of doctors and nurses who inspected the slums every summer, the King’s Daughters soon began offering additional services such as sewing classes, mothers’ clubs, health care, summer camp, and a penny provident bank.

In 1892, with Riis’ help, the King’s Daughters Settlement relocated to 48 Henry Street, where it remained for the next 58 years. At a celebration of the 25th wedding anniversary of Jacob and his first wife Elisabeth Riis in 1901, Bishop Henry Codman Potter announced that the King’s Daughter’s Settlement would be renamed the Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement.